Yes, your brain is a machine—if you choose to see it that way

As a Nobel Prize physicist pointed out, our method of study determines what we learnAnil Seth, a Professor of Cognitive and Computational Neuroscience at the University of Sussex, gave a TED talk recently (linked below) in which he asserted that “the combined activity of many billions of neurons—each one a tiny biological machine—is generating our conscious experience…”

So, is your brain really a biological “machine”? Or is that just an analogy, like saying that a restaurant kitchen is a “hive” of activity? If so, how good is the analogy? Why do we select the analogy of a “machine” rather than a different one? It’s an important question, as we will see, because the questions we ask of nature constrain the answers we obtain.

A machine is an artifact. It is a human-built assembly of materials that have no natural inclination to work in unison. Silicon and copper, plastic and glass have no natural propensity to compute. We make artifacts, for example computers, out of these materials to serve our purposes. But they are not the materials’ natural purposes.

In the classical hylemorphic (Aristotelian) perspective, an artifact is an artificial composite of substances and thus it has an accidental, not substantial, form. Machines work as they do “accidentally”; that is, their function as machines is not inherent to the matter that comprises them. Rather their function is imposed on the disparate parts by human intelligence.

In this sense, obviously, the brain is not a machine. Unlike a machine, the brain is an organ, a functional part of a living organism. It (along with the body) has a substantial form; its activity is natural to it. One might say that the brain’s activity is intrinsic to it, not imposed on it extrinsically, as is the activity of a machine.

In this sense, obviously, the brain is not a machine. Unlike a machine, the brain is an organ, a functional part of a living organism. It (along with the body) has a substantial form; its activity is natural to it. One might say that the brain’s activity is intrinsic to it, not imposed on it extrinsically, as is the activity of a machine.

Of course, there are some analogies between the human brain and a machine. Each has parts that work together, each has volume and mass, and each can be understood in part by understanding the parts that comprise it. But Dr. Seth’s analogy between the brain and a machine is as much the consequence of his metaphysical bias—his view of nature as inherently mechanical—as it is of the actual similarity between the brain and a machine.

What the brain “is” depends on your metaphysical perspective. The ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus (late 6th century BC) was a material monist who believed that all things were modifications of fire—the exothermic metabolism of the brain would no doubt have led him to affirm that the brain was, essentially, fire. Thales (6th c. BC) believed that everything was water. The fact that the brain is semi-liquid, has a specific gravity of roughly one, and that most of the brain is water would certainly lead Thales to exclaim ‘the combined fluidity of many billions of neurons—each one a tiny water drop—is generating our conscious experience…”.

French philosopher René Descartes saw the material world (res extensa) as a machine, although he would have insisted that the brain is like a transistor radio, with the antenna (for reception of the res cogitans) in the pineal gland. Biologist Don Ingber at Harvard has noted (personal communication) that the brain has many properties of a contractile organ—it is full of microfilaments and microtubules. The brain is, structurally, like a muscle.

Other analogies come to mind. A football fan would note that the brain is roughly the size, weight, and shape of a football, although it would surely be slippery to throw and catch. A gourmet might insist that the brain is like gelatin in a bowl (the skull)—he could point to experiments modeling head injury in which gelatin is used to simulate brain tissue.

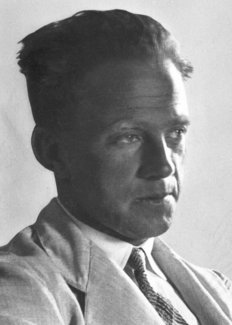

What the brain “is” depends on how you study it. We live in a mechanical age, so we study it as a machine. But our method of study determines what we learn. Theoretical physicist and Nobel laureate Werner Heisenberg noted perceptively that “…what we observe is not nature itself but nature exposed to our method of questioning” ( Physics and Philosophy: The Revolution in Modern Science, 1958, p. 78).

By its nature, the brain is an organ. It is a functional part of a living being. We can draw analogies to it in order to help us understand it, but we must remember that what we then learn about the brain is only that aspect of its nature that is exposed to our method of questioning.

In other words, the brain will seem like a machine if we study it like a machine. We live in a mechanical age so it is no surprise that the brain seems like a machine to us. It is not entirely illogical to study the brain as a machine but we must remember that the answers we obtain will be as biased as the questions we ask.

One has a sense that, like many neuroscientists, Dr. Seth doesn’t really understand his own bias. The brain is an organ in a living being, not a machine. It is irresponsible to compare it to a machine without an emphatic proviso that such study will mislead us unless we understand our own (largely unwarranted) mechanical bias.

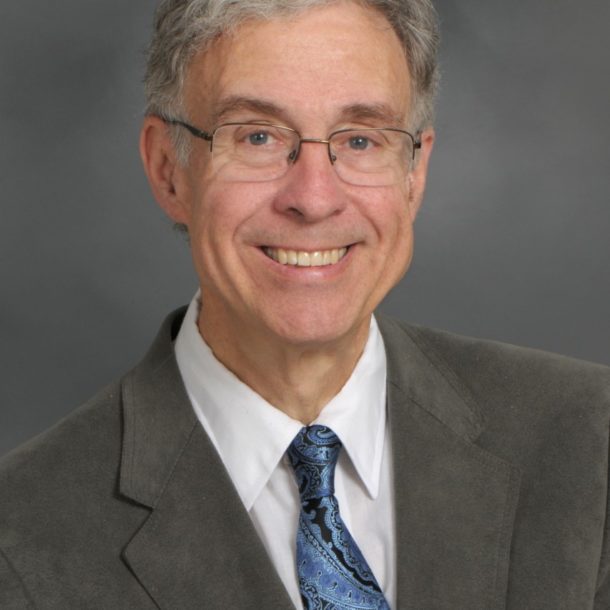

Michael Egnor is a neurosurgeon, professor of Neurological Surgery and Pediatrics and Director of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Neurological Surgery, Stonybrook School of Medicine

Michael Egnor is a neurosurgeon, professor of Neurological Surgery and Pediatrics and Director of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Neurological Surgery, Stonybrook School of Medicine

Also by Michael Egnor: Does your brain construct your conscious reality? Part I

A reply to computational neuroscientist Anil Seth’s recent TED talk

Does your brain construct your conscious reality? Part II In a word, no. Your brain doesn’t “think”; YOU think, using your brain

and

The brain is not a meat computer. Dramatic recoveries from brain injury highlight the difference