Is the Tech Industry Destroying the Free Market?

The internet drifts toward monopoly control due, in part, to its structure, not merely due to tech moguls’ plansSome analysts sound the alarm about the tendency of big tech to drift toward monopoly:

The reality, though, is that monopolies are a cancer on capitalism. They limit competition and lead to abuses of power. In truly free markets, competition causes a constant churn and makes it difficult to be complacent in service, quality, or innovation; it creates checks and balances.

Vivek Wadhwa, “The tech industry is getting away with the murder of capitalism” at MarketWatch

The reason that the internet drifts toward monopoly control is related to its structure as well as to business leaders’ intentions. Let’s have a closer look.

Most concerns about monopoly focus on the way content is produced, moderated, and sold. While content providers do use filtering, suggestions, and algorithm adjustments to “manage” discussion and control the Overton window of permitted opinion, there is a deeper layer that is not always factored in: the control providers have over content impacts the physical infrastructure of the internet.

The infrastructure of the Internet is largely hidden in undersea cables and buildings you would not recognize. The logical network that overlays the physical infrastructure is even harder to see. This “hiddenness” makes it hard to visualize how the Internet is shaped and reshaped and how reshaping impacts the services, like social media and shopping, that ride on top of it.

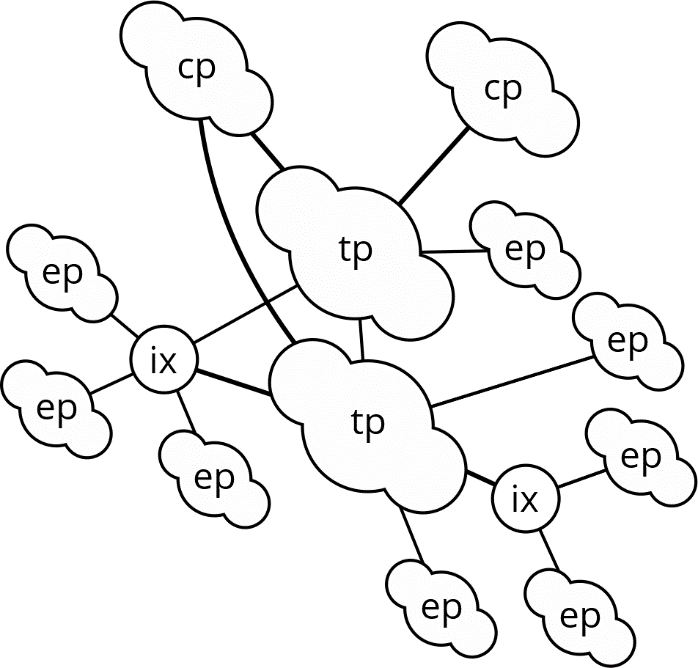

From the beginning, the internet has comprised organizations working together to build and interconnect regional and global networks. Each of these networks is assigned an autonomous system, which not only identifies the network but also allows routing protocols to discover and advertise the locations of devices connected to the internet. For many years after the internet became a business proposition, operators organized different kinds of providers in a scale-free tree. Here is an illustration of the system, which includes transit providers (tp), edge providers (ep), internet exchanges (ix), and content providers (cp):

The trouble was, companies found it hard to make money just by building networks and carrying bits this way. Content is what makes money, not transport. And the speed at which content loads makes a big difference in whether users stay involved (user engagement).

The fact that content plus speed determines profit works against the “scale-free” structure of the early Internet, pictured above. Here’s why: A user connected to one of the edge providers (ep in the diagram above) must pass through the provider’s network, through a connection point to a transport provider (to in the diagram above), through the transport provider’s network, then through a connection point to a content provider’s network. In many cases, the data that the user has requested will pass through several internet exchanges ( ix in the diagram above), as well.

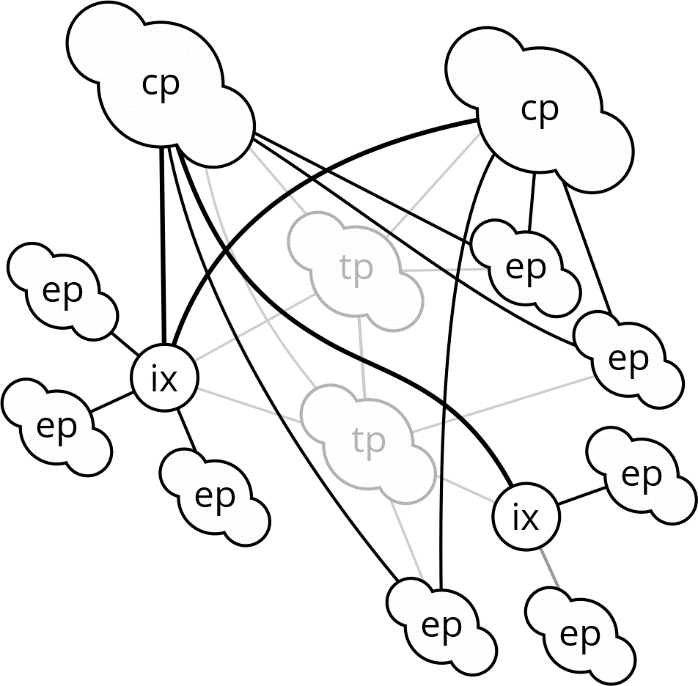

Each of these “hops” slows down data transfer speed. Each provider must be paid for transporting the data, as well. The content provider, then, is hit with a “double tax”; the first impacts customer engagement and the second impacts profit margin. To work around these two problems, content providers started building their own largescale networks. Rather than connecting to their users through transit providers, they began connecting directly to the edge, or as close to the edge as possible, as shown in the diagram below.

This trend has been developing for many years.

Routing service around transit providers has multiple effects. First, any new service trying to produce or serve content is at an immediate disadvantage in terms of speed of load time, and therefore user engagement. Thus, the established, large-scale content providers have an economic edge. Centralization of power over content becomes “natural” over time.

Second, as transit providers are “defunded” when major content providers bypass them, the core of the Internet is weakened. This can become a cycle in which decreasing investment at the core causes load times across transit providers to increase. That, in turn, causes content providers to bypass transit providers in more markets, which then causes investment in the core to decrease once again, etc.

Third, content providers naturally want infrastructure where they can reach the most users at the lowest cost. This means densely populated areas will receive better service than more rural areas. One result is depopulation of rural areas which, arguably, has severe negative social impacts.

This chain of events bears on the “net neutrality” debate, as well; in some cases, “net neutrality” means simply that content providers do not want to share the rich data they collect on users with edge providers.

What about solutions? Content providers are just doing what makes sense from their perspective—they want to reach their users more quickly and cheaply. One possible solution is to separate physical network connectivity from content provision, using regulation. Because the physical transport of bits is not generally profitable, this solution might involve government subsidies (perhaps just tax breaks). The problem is, of course, that it places control over access to all electronic services in the hands of various government organizations. That might be a problem for protest movements and for those attempting to defend themselves against government oppression.

Another potential solution could be the rise of edge computing, which distributes all data as close to the edge as possible. Perhaps a realistic path forward might be some form of regulation that encourages edge computing, particularly in more remote areas, and encourages local bandwidth cooperatives in more rural areas, along with community networks.

However we may feel about any of the suggested proposals, when we seek to counter the centralization of information in large-scale content providers, we cannot ignore the physical infrastructure that supports it.

Note: “How the internet really works” provides a helpful summary of the internet’s main organization.

Also by Russ White:

Why you can’t just ask social media to forget you While we now have a clear picture of the challenges current social media pose to peoples and cultures, what to do is unclear

Is deep virtual reality the next big market disruptor? When media moves from capturing attention by being different to capturing ever smaller slices of users’ time, the market is ripe for disruption

and

Will Facebook’s new focus on “community groups” prevent abuses? When you look a little closer at the proposal, you will see that the answer is no.