Researchers: Our Conscious Visual Perception Lies Outside Our Visual Cortex

They concluded that the end step of perceiving where objects are occurs in the frontal lobes, a finding they describe as “radical”A recent study finds that, contrary to expectations, our visual cortex (in the back of the brain) processes what we literally see but that the frontal lobes interpret it for us:

A new study finds that the conscious perception of visual location occurs in the frontal lobes of the brain, rather than in the visual system in the back of the brain. The results are significant given the ongoing debate among neuroscientists on what consciousness is and where it happens in the brain.

Dartmouth College, “Conscious visual perception occurs outside the visual system” at ScienceDaily

For the paper — Sirui Liu, Qing Yu, Peter U. Tse, Patrick Cavanagh, Neural Correlates of the Conscious Perception of Visual Location Lie Outside Visual Cortex. Current Biology, 2019; 29 (23) — researchers scanned participants’ brains using fMRI while the participants were subjected to an optical illusion generator called a Gabor patch:

For one of the tasks, participants were asked to stare at a fixed black dot on the left side of the computer screen inside the scanner while a dot that flickered between black and white, known as a Gabor patch, moved in the periphery. Participants were asked to identify the direction the patch was moving. The patch appears to move across the screen at a 45 degree angle, when in fact it is moving up and down in a vertical motion. Here, the perceived path is strikingly different from the actual physical path that lands on the retina. This creates a “double-drift” illusion. The direction of the drift was randomized across the trials, where it drifted either towards the left, right or remained static.

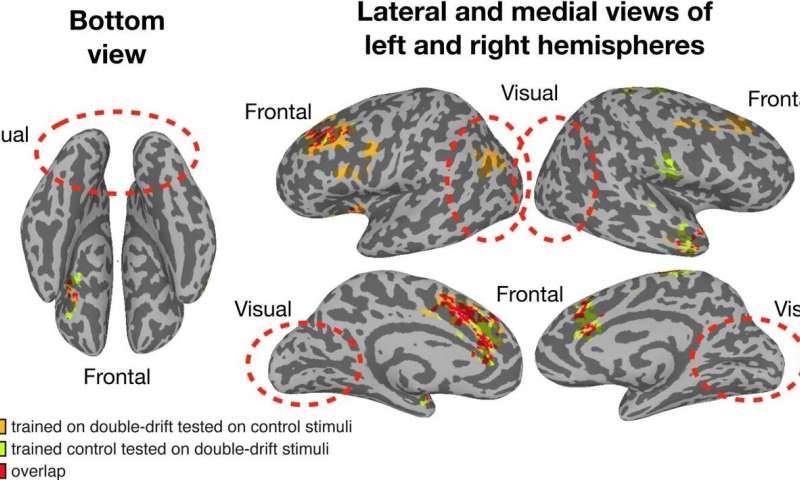

Using fMRI data and multivariate pattern analysis, a method for studying neural activation patterns, the team investigated where the perceived path, tilted left or right from vertical, appears in the brain. They wanted to determine where conscious perception emerges and how the brain codes this. On average, participants reported that the perceived motion path was different from the actual path by 45 degrees or more. The researchers found that while the visual system collects the data, the switch between coding the physical path and coding the perceived path (illusory path) takes place outside of the visual cortex all the way in the frontal areas, which are higher-order brain regions.

Dartmouth College, “Conscious visual perception occurs outside the visual system” at ScienceDaily

What the participants thought they were seeing was accompanied by activity in their frontal lobes. Study co-author and co-principal investigator Patrick Cavanagh told media that the researchers have concluded that “frontal areas are critical to the emergence of conscious perception.” That is in addition to their widely accepted roles in decision-making and thinking: “Our findings suggest that this area of the brain is also the end step for perceiving where objects are. So, that’s kind of radical.”

If the study replicates, it demonstrates, once again, that the brain is not strictly compartmentalized; a number of different parts play roles in providing us with information, illusory or otherwise.

There is also a phenomenon called blindsight: People whose visual cortex is damaged but still have sound eyes sometimes gain the ability to “sense” objects that they are not aware that their eyes see. Their functional eyes seem to adapt working with parts of the brain that can provide signals but are not consciously experienced as such. Then the person who “somehow knows” there is something in a visual field is right far more often than chance would explain.

A major consequence of the advance of modern neuroscience is that we now “know” so much less than we used to. Even basic facts about the human brain are now hotly contested. But what we do know points us in promising research directions.

We’ve had to confront fundamental questions like these: Is a brain really needed for thinking? The protist “blob” on display at the Paris Zoo this past year forces the question. Amoeba slime molds can, like the famous Parisian “blob,” behave as if they were a single thinking organism though no individual brain is involved. And plants turn out to have such complex communications without a brain that plant scientists have felt the need to stress that plants are not conscious.

But the human brain features greater surprises still. Some human beings think and speak with only half a brain. And, speaking of human brains, Michael Egnor notes that a range of neuroscience research findings is more readily explained by assuming that some aspects of thought –– abstract intellectual thought and free will –– are immaterial. This whole area is a serious challenge to materialism, the dominant perspective in science.

If anything, problems around the relationship between the mind and the brain may intensify in number and complexity over the next decade. The more we learn, the less we “know,” the way we used to. Perhaps we are like mountain climbers congratulating ourselves on scaling the nearest local mountain peak in a chain, leaving the foothills behind. Then we look out on the other side and what do we see?

As a poet once put it,

A little learning is a dangerous thing;

Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring:

There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,

And drinking largely sobers us again.

Fired at first sight with what the Muse imparts,

In fearless youth we tempt the heights of Arts,

While from the bounded level of our mind

Short views we take, nor see the lengths behind;

But more advanced, behold with strange surprise

New distant scenes of endless science rise!

So pleased at first the towering Alps we try,

Mount o’er the vales, and seem to tread the sky,

The eternal snows appear already past,

And the first clouds and mountains seem the last;

But, those attained, we tremble to survey

The growing labors of the lengthened way,

The increasing prospects tire our wandering eyes,

Hills peep o’er hills, and Alps on Alps arise.

Alexander Pope (1688–1744), “A Little learning is a dangerous thing” at Poetry Nook

The best evidence that we are making progress is in fact that today we “know” so much less than we once did.

Further reading on the human brain and mind:

Why the brain is not at all like a computer. Seeing the brain as a computer is an easy misconception rather than an informative image, says neuroscientist Yuri Danilov. Nor is it billions of little computers. That said, the brain exceeds the most powerful computers in efficiency.

How the injured brain heals itself: Our amazing neuroplasticity

High tech can help the blind see and amputees feel. Recently, six completely blind people have had their vision partially restored at the Baylor College of Medicine by Orion, a device that feeds camera images directly into the brain via electrodes, bypassing damaged optic nerves. It’s not a miracle; the human nervous system can work with electronic information.

and

New mind-controlled robot arm needs no brain implant. The thought-controlled device could help people with movement disorders control devices without the costs and risks of surgery.