Serious Media In China Have Gone Strangely Silent

With a compulsory new app, the government can potentially access journalists’ phones, both for surveillance and capturing dataIn China, 2019 was a bad year for media freedom. The 2019 World Press Freedom Index compiled by Reporters without Borders ranked China 177 out of 180 countries, ahead of Eritrea, North Korea, and Turkmenistan.

The Committee to Protect Journalists reported that by the end of 2019 China had jailed forty-eight journalists. All but one were local reporters. The Committee ranks China as the number one country for most journalists jailed, followed by Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt (December 11, 2019) But the very fact that China appears on these lists is censored in that country’s media.

Last year, one embattled Chinese journalist, Liu Hu, told the New York Times that investigative journalists are “almost extinct” in China. Liu’s own story helps us understand why: He was detained for a year for reporting on government corruption and was one of the journalists who have been reprimanded for reporting on crimes, accidents, or corruption by state officials or agencies. He believes that the government has kept citizens in the dark in order to foster social unity and stability.

Censorship in China

Since Xi Jinping became president in 2012, online and print media have largely abandoned investigative journalism. Regulations on what may be published have only increased. China has one of the most extensive censorship and propaganda machines in the world. Not only are websites, such as Facebook, Twitter, and Google, inaccessible because of China’s Great Firewall, but news websites and social media outlets must obtain permission to publish news from the Cyberspace Administration of China, an arm of the Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission headed directly by President Xi. The Publicity Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, or directly translated from the Chinese—the Central Propaganda Department—monitors journalists and news outlets to ensure that the media follow its ever-growing list of rules.

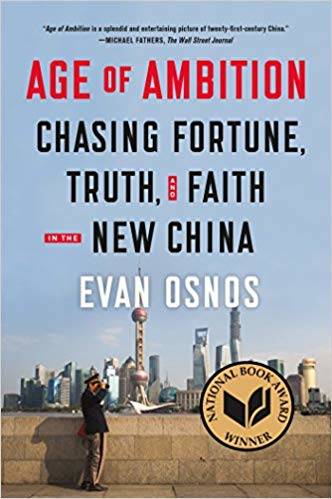

In Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth, and Faith in the New China (2014), journalist Evan Osnos reported that the Central Publicity Department is housed in a large non-descript building in Beijing near other government offices on the Avenue of Eternal Peace. But the building did not have an address and was not on any list of government buildings:

“The ‘Publicity’ in the title was for English purposes; the Chinese name was the Central Propaganda Department, and it was one of the People’s Republic’s most powerful and secretive organizations—a government agency with the power to fire editors, silence professors, ban books, and recut movies.” (Osnos, 117)

According to Osnos, China committed itself to propaganda after the events at Tiananmen Square in 1989:

Nothing consumed more of the Department’s attention than the press. ‘Never again,’ President Jiang Zemin vowed after Tiananmen, ‘would China’s newspapers, radio, and television be permitted to become a battlefront for bourgeois liberalism’… Journalists were still expected to ‘sing as one voice,’ and the Department would help them do so by issuing a vast and evolving list of words that must and must not appear in the news.” (Osnos, 119)

Let’s look at the recent reports on the free flow of information in China in this context:

Foreign Journalists

The Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China (FCCC), a Beijing-based group and with over 200 correspondents from 30 countries and territories, released its 2018 annual report on media freedoms in China (full report here).

According to the report, 91% of FCCC journalists surveyed “were concerned about the security of their phones” while working in China and 66% “worried about surveillance inside homes and offices.” Twenty-two percent knew that the government authorities had tracked them or their sources using public surveillance systems, such as cameras and facial recognition technology.

Xinjiang (the Uyghur Autonomous Region), in particular, posed a problem for journalists. Officially, journalists are allowed to travel anywhere within China except for the Tibet Autonomous Region. But in practice, at least in the last couple of years, journalists have been restricted from reporting in Xinjiang. (They are also restricted from reporting near China’s border with North Korea.)

In 2018, when Xinjiang had been in the news because of the construction of internment camps for Uyghurs and other minorities, several journalists who tried reporting in Xinjiang were tailed by government officials or the police during their time there. One journalist knew that the government was tracking his travels using license plate monitoring. Others were pressured into deleting pictures from their phones by a plainclothes police officers posing as a civilian who wanted a photo removed for “privacy” reasons.

In one egregious incident, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs essentially kicked Buzzfeed’s Middle East correspondent Megha Rajagopalan (below) out of the country. Despite having worked six years in the country, after she had published a major story on the detention camps in Xinjiang, she could not renew her visa.

Other journalists have faced problems with visa renewal and several reported having to sit through an hours-long tirade at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs before they could get their visa. For example, Matthew Carney of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, granted a two-and-a-half month visa rather than the typical year, was informed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that his short projected stay was due to his reporting in Xinjiang. Carney also reported that someone had opened and moved files on his computer in the middle of the night. He also revealed that his Chinese assistants “were routinely told by security personnel that they are traitors working for the foreign press and advised them to consider the consequences. They were told they are unpatriotic and should consider their future.” (Under Watch, page 8)

Other correspondents reported similar stories regarding the risks run by their Chinese assistants. Beijing bureau chief for the Financial Times, Tom Mitchell said, “The overall climate continues to deteriorate to the point where we are really worried about the safety of contacts and Chinese-national researchers…It’s by far the worst I’ve seen working as a journalist in China or Hong Kong since 2000.” (Under Watch, page 2)

FCCC president Hanna Sahlberg has warned that Chinese authorities have become more sophisticated in their use of surveillance: “The wider monitoring and pressure on sources stop journalists even before they can reach the news site… There is a risk that even foreign media will shy away from stories that are perceived as too troublesome, or costly, to tell in China.” (Under Watch, page 2)

Chinese Journalists

Many Chinese nationals who work as journalists act as Communist Party cheerleaders. Not only must they avoid sensitive topics such as government corruption or the Tienanmen Square massacre but they must also promote stories about the strength of the economy and unity within the Party. With the Chinese New Year celebrations approaching, the Chinese media will likely headline positive stories while downplaying negative ones with the aim of highlighting the government’s accomplishments over the last year.

In 2019, the All-China Journalists Association published a new code of ethics that requires journalists to paint China is a good light to international readers, as well as serve the party’s interests, among other things. To ensure that they uphold the code of ethics, Chinese journalists must familiarize themselves with the content on the Xi Study Strong Nation app, which all government employees are required to download and use. The app’s name is a play on the Chinese word for “study,” which also contains the president’s name, and familiarizes the users with “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era.” At the end of the year, journalists were told, they would need to take a test of their loyalty to get their press cards renewed.

Characteristically, last October, a German cyber-security firm found that the loyalty app contained code that gave the “super-user” (i.e., the Chinese government) access to users’ phones. In short, the government can potentially access journalists’ phones, both for surveillance and capturing data.

Liu Hu sums up the scene in a few words: “Outside of China, journalists are fired for writing false reports… Inside China, they are fired for telling the truth.”

Author’s note: The Committee to Protect Journalists offers a helpful summary of how censorship works in China here:

More from Heather Zeiger on high tech surveillance and freedom in China:

China: DNA phenotyping profiles racial minorities In the United States, targeting minorities means political pushback; in China, no such discussion is allowed.

Tienanmen Square 30 Years On: Words Still Have Power Back then, students fought oppression via the fax. They depended on free media in Hong Kong to tell the world

Hi-tech Freedom Game in Hong Kong: Technology can oppress a people group or it can give them a voice

Can China really silence Hong Kong?

The unadvertised cost of doing business with China: It’s a big market, with one Big Player, and some strange rules. In China, censorship includes democracy, human rights, sex, George Orwell’s 1984, and Winnie-the-Pooh (because the stuffed literary bear has been compared by some Chinese bloggers to their President). Such censorship, say many, minimizes the value of the internet.

China: What You Didn’t Say Could Be Used Against You An AI voiceprint could be used to generate words never said.

In China, high-tech racial profiling is social policy. For an ethnic minority, a physical checkup includes blood samples, fingerprints, iris scans, and voice recordings. The Chinese government seeks a database of everyone in the country, not only to track individuals but to determine the ethnicity of those who run up against the law.

Also: Hong Kong: The dread that lies ahead They fear the fate of the Uyghurs, under “complete video surveillance” (News)