Centralization Is Not Inevitable

Even technology is not inevitable; it comes and goesIt seems I came back from the long weekend with the “contrarianvirus.” In particular, I want to respond to a recent Analysis post: Technology Centralizes by Its Very Nature.

Let me begin by clarifying my position: First, I do not view centralization as an inherent evil, anymore than fiat currency (issued by government) is an inherent evil. Second, it is no secret that communism and socialism both depend on increasingly centralized control of every aspect of our lives in their “scientific” pursuit of ultimate control. By contrast, classical economic theorists like Adam Smith and Friedrich Hayek argue that centralization is both unwarranted and a failure. Hayek’s last book, The Fatal Conceit (University of Chicago, 1991) is an instructive read. Third, I do not believe that centralization is inevitable, necessary, or even irreversible.

Hayek’s point in Fatal Conceit is that price is a compromise between what the producer of goods can afford and how badly the consumer wants them. There’s no way to know the “right price” beforehand; it is an intrinsically human quality. Therefore it is a “very bad thing” to use central planning to enact price controls in an attempt to skew the equation. This is not to say that every government on this planet has not used quotas, taxes, incentives, or advertising to do that very thing. But when governments do attempt centralized control, economic disasters like Venezuela are more the norm than the exception.

Analysis offers a picture of the way technology is constantly centralizing—predicting price points, controlling access, limiting competition, etc. It reads like the dystopian vision of George Orwell’s 1984 or Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. And it ends with

I confess, I’m flummoxed. To me, to say that technology grows is tantamount to saying that we all die or that love and war seems to capture the important gritty stuff in life. Or that Shakespeare was a good poet. Truisms. The problem is that technology masquerades as malleable and decideable and controllable, as wars may sometimes masquerade as predictable and avoidable to naive Pollyanna. We should call out China’s aggressive moves to track its citizens and intimidate them in various ugly ways, no doubt. But so too, should we all “call out” the modern world. New ideas are needed. The problem is much deeper than AI itself. Anyone?

The irony of this piece is that Analysis has often written about the limitations of AI, about its inability to carry out human interactions, yet here despairs over its inevitable “progress” in economics and warfare. Let me suggest that both economics and warfare are peculiarly human behaviors, as are reproduction, care of the young and the aged, and cooking. The very same limitations outlined in previous posts apply even more to economics and warfare.

History is the great teacher, so permit me a tour of history. The “Indus River” civilization (3300-1300 BCE) boasted advanced irrigation and planned cities when it vanished, leaving behind a comparatively primitive existence for nomads. It was only rediscovered three millennia later. The Egyptians didn’t vanish but their technology of pyramid building and their intricate orthography disappeared for over 1500 years. The Romans built aqueducts that have lasted in some places for 2000 years. Yet the technology of cement and underwater concrete that the Romans used remained lost for 1600 years or more, preventing even the repair of existing aqueducts. The Byzantine Greeks invented “Greek fire,” a weapon that defended their civilization from overwhelming numbers of foes for roughly 750 years. Yet today we have no idea what it was.

So no, nothing lasts forever, not even technology. Even centralization comes and goes. When companies merge and later divest, economists call it a cycle. When innovation stagnates, there tends to be a similar merger and centralization cycle. When innovation “moves fast and breaks things,” there tends to be a decentralization cycle. Neither cycle is permanent. Let’s apply this observation to some current questions:

Will China undergo such a “decentralization” cycle?

Absolutely. The coronavirus has demonstrated that centralization has its limits. If you recall, President Herbert Hoover initiated “central planning” as a way to prevent downturns in the economy. The Great Depression in America lasted 10 years longer than the short 2-year depression in Europe—due to Hoover/Roosevelt’s central planning. I predict that when the dust settles on this coronavirus outbreak, the order-of-magnitude greater death rate in China, compared to the 2003 SARS outbreak, will be blamed on central planning. As a consequence, look for China to decentralize its health care policies—making individual hospitals responsible for declaring quarantine and establishing local storage of gowns/masks/medical supplies.

Will the same be true of the internet?

The author of the Analysis piece needs to read George Gilder’s latest book, Life after Google: The Fall of Big Data and the Rise of the Blockchain Economy. It would also be instructive to re-read his 2000 book Telecosm to understand what was broken in order to achieve the Internet.

But what prophet can ever predict the future perfectly?

No one. That’s why I began by saying that centralization is not the demon that leads to communism. On the contrary, it is communism that chases after the idol of centralization, distorting it into its own image. No one can predict how that centralization will be used in the future.

Here is the Analysis piece to which Robert Sheldon is responding:

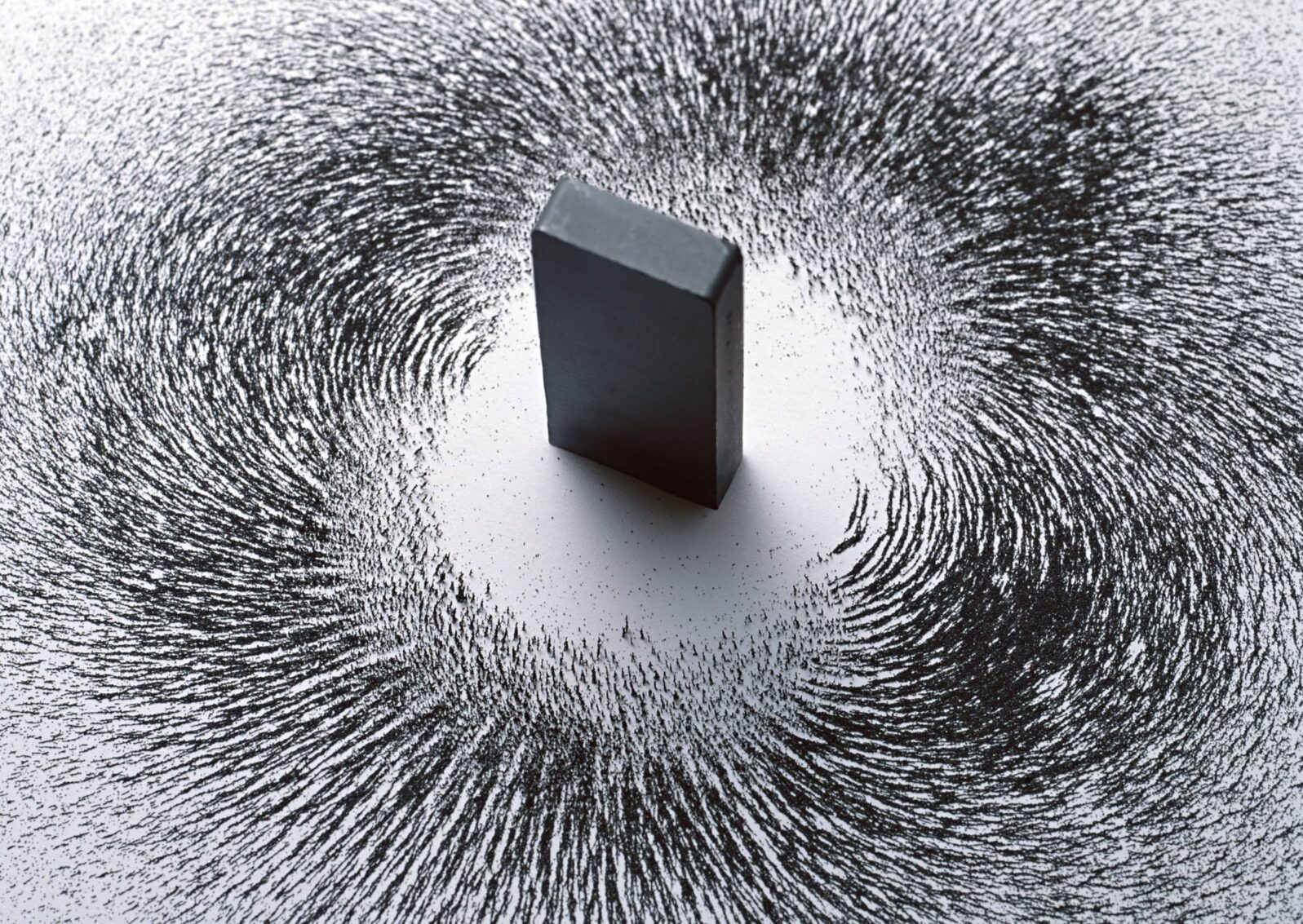

Technology centralizes by its very nature. Here are some other truths about technology, some uncomfortable ones. To see what I mean about centralization, consider a non-digital tool, say, a shovel. The shovel doesn’t keep track of your shoveling, read your biometrics, and store a file on you-as-shoveler somewhere. It’s a thing, an artifact. So you see, the new digital technology is itself the heart of the surveillance problem. No Matrix could be built with artifacts.

You may also enjoy this Analysis piece:

The danger AI poses for civilization: Why must Google be my helicopter mom? If I have a coffee cup with “AI inside,” it’s probably connected to the Internet, which is just another way of saying that my coffee cup is transmitting data to some company’s servers about my coffee drinking habits. Whatever benefit the app provides will come at a cost to my autonomy, privacy, and competence as a person.