The Political Case Against Self-Driving Cars

An auto mechanic turned philosopher warns against ceding control of one’s destination to others, in the relentless pursuit of safetySome worry about the role driverless cars might play in the next pandemic lockdown (there will be other pandemics and emergencies). David Lanza offers a thought-provoking scenario for these autonomous/self-driving vehicles:

The production of driverless cars remains in its infancy, but if those cars ever become common, the government will have no problem locking us down on the slightest pretext. Driverless cars have no steering wheels and depend upon pre-programmed GPS coordinates to guide them (and us) to our destinations. Aside from entering a destination at the start of a trip, a driver has no way to direct the car.

David Lanza, “Driverless Cars Will Make the Next Pandemic Crackdown Complete” at American Thinker

The response to the COVID-19 crisis, he reminds us, was characterized by banning or forbidding a perplexing variety of different things in different jurisdictions—garden seeds here and singing in church there. And “non-essential” businesses were shut down:

When future governors create a list of “non-essential” businesses, those businesses will be instantly unreachable by vehicle. Your car’s GPS system will not accept an address for any business on the banned list. You will have no way to make your car go to those places. If you are the owner or employee of a “non-essential” business, your car’s GPS might not work at all for you. There will be no one with whom to argue. Protests will not matter. There will be little possibility of evading the rules.

Police will not have to visit churches. No cars will go to a church.

David Lanza, “Driverless Cars Will Make the Next Pandemic Crackdown Complete” at American Thinker

Will our driverless cars really become our “jailers” via “a few keystrokes from computer programmers working for the tech giants,” with little or no recourse, as he predicts? Well, first, there is room for reasonable doubt that driverless cars will advance to that level of competence any time soon or ever.

Apart from serious AI issues like how to teach computers common sense, the decision could come down to economics in the end. Suppose it costs $50 trillion dollars to solve all the problems that prevent cars from being fully self-driving everywhere but only $3 trillion to enable them to be self-driving on major arteries with virtual rails? Are many people likely to see the pursuit of full self-driving as worth the humongous expense?

Right now, we’re still a long ways off. Recently, a German court told Elon Musk to quit claiming that his vehicles are autonomous (they’re not). That won’t deter relentless boosters. But if we follow the court’s lead in promoting accuracy, let’s look more carefully at what self-driving cars will really do.

Bryan Mistele presented a much sunnier view in a recent discussion with Jay Richards:

It’s likely just an automated Uber. So, when you go from point A to point B in an urban area, it’ll basically take you from where you are to where you need to go. Primarily, initially, in the major urban area. So New York, San Francisco, that are well mapped, well defined problems. It’ll be a long time until you have vehicles that can drive 100% of the time, in any conditions, gravel road, things like that.

News, “If self-driving cars become the norm, what will it feel like?” at Mind Matters News

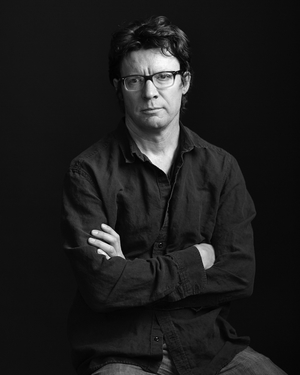

Are there differences driverless cars would make to our way of thinking about ourselves even if no totalitarian state attempts to control our mobility? Matthew Crawford, an auto mechanic who is also a philosopher, explains why he thinks so in Why We Drive: Toward a Philosophy of the Open Road (June 2020). In a review essay, Patrick Keeney, associate editor of the C2C Journal, reflects on the questions that Crawford, whom he calls “a proud, knowledgeable and unapologetic gearhead” with a Ph.D. in political philosophy, raises:

According to the advocates of driverless cars, by ceding control of our vehicles to impersonal algorithms, there will be fewer traffic jams, fewer accidents, less parking congestion, fewer highway fatalities, and less harm to the environment. It’s an impressive list and a coup of some consequence. Or perhaps it’s impressive insofar as we are willing to accept the boosterism of the technocratic elites promoting driverless cars.

Patrick Keeney, “Why The Freedom Of Driving Still Matters” at C2C Journal

Keeney, sympathetic to Crawford’s view, doesn’t find the elite’s vision reassuring:

With driverless cars, we are about to change our status from drivers, individuals who exercise agency and find joy in perception, steering, navigation and decision-making – our very own daily form of captaincy – to passengers who are subject to a new system of algorithmic control with no room for human agency. We are in danger of becoming a new class of administrative subjects who will be managed by an “all-colonizing” technocratic elite. Crawford raises the perplexing question of why the world’s largest advertising agency, Google, should be making such a massive investment in driverless cars. The answer is disturbing:

“By colonizing your commute, the patterns of your movement through the world will be made available to those who wish to know you more intimately – for the sake of developing a deep, proprietary science of steering your behaviour. Self-driving cars must be understood as one more escalation in the war to claim and monetize every moment of life that might otherwise offer a bit of private head space.

Patrick Keeney, “Why The Freedom Of Driving Still Matters” at C2C Journal

Crawford acknowledges that the very elements he finds disturbing will be welcomed by those who are “convinced of the innate superiority of digital technology over the human mind,” and he calls their view “safetyism”:

The debate about the driverless vehicle, then, is about more than merely its costs, complexity, convenience or whether it can be made truly safe. It represents another battle in the ongoing war between technocratic security (or at least the promise thereof) and human freedom. A recurring theme in the book is the attempt by politicians and automakers to make cars safe and immune to human error. Dmitri Dolgov, head of Google’s Self-driving Car Project, claims that human drivers need to be “less idiotic.” In the public mind, automation is joined to the moral imperative of safety, neither of which admits any limit to its expansion. “Safetyism” is a closed-loop, designed to reduce human idiocy and increase human security by legitimizing ever-more automation.

Patrick Keeney, “Why The Freedom Of Driving Still Matters” at C2C Journal

One problem with the pursuit of safety as our key societal goal is that it can lead to diminishing returns with high collateral damage. John Ioannidis created considerable controversy recently when he identified that tendency as a problem with much of the COVID-19 response:

Flattening the curve to avoid overwhelming the health system is conceptually sound — in theory. A visual that has become viral in media and social media shows how flattening the curve reduces the volume of the epidemic that is above the threshold of what the health system can handle at any moment.

Yet if the health system does become overwhelmed, the majority of the extra deaths may not be due to coronavirus but to other common diseases and conditions such as heart attacks, strokes, trauma, bleeding, and the like that are not adequately treated.

John Ioannidis, “A fiasco in the making? As the coronavirus pandemic takes hold, we are making decisions without reliable data” at Stat (March 17, 2020)

.

Canceling cancer surgeries during a lockdown, for example, might lead to the collateral damage of preventable deaths down the road—deaths that are never directly attributed to any specific public decision about COVID-19. In the same way, relentless pursuit of safety through driverless cars may inadvertently create new risks.

Keeney ends by wondering whether we need “an adaptation of the human spirit, to make it more smoothly compatible with a world that is to be run by a bureaucracy of machines,” not that he would wish such an adaptation on himself.

Crawford (right), who once owned as motorcycle shop, is also the author of Shop Class as Soulcraft, which makes the case for the value and dignity of blue collar work as an engagement with the real world around us in a world of increasing digitization. He has found a sympathetic ear in philosopher John Gray, who considers Why We Drive “one of the most original and mind-opening studies of practical philosophy to have appeared for many years”:

Driving is not just a means to the end of getting from one place to another. For many people it is, or can be, an important part of the good life. “To drive is to exercise one’s skill at being free,” Crawford writes at the close of Why We Drive, “and one can’t help but feel this when one gets behind the wheel. It seems a skill worth preserving.”

In this view, which Crawford finds prefigured in Immanuel Kant’s understanding of rational autonomy, human beings are free to the extent that they are not exposed to contingency and accident. But such an idea of freedom requires an imaginary separation from our bodies, which are inherently accident-prone, and from the instinctive responses for dealing with their fragility that are built into them. Environments designed to eliminate danger from our lives impair abilities that are essential to our humanity. The need for security and risk-control is real enough, and at times overriding. But displacing human skill and agency does not always enhance safety, and when applied across society it has the dystopian effects to be expected from a technocratic ideology.

John Gray, “The case for taking more risks” at Unherd

There is no clear historical precedent for a society in which almost all vehicles are autonomous. It is as well to reflect on the many different directions in which mass adoption of self-driving vehicles may take us, especially if they take us to places we do not really wish to be.

You may also enjoy:

If self-driving cars become the norm, what will it feel like? Already, Millennials are more likely than their parents to see transportation as simply a means to an end. Jay Richards explores what we can expect in the near future with transportation analyst Bryan Mistele

Have Millennials broken up with America’s car culture? They are less likely to have licenses; they prefer ride-sharing, says auto data analyst

AT&T CTO says, yes, you can live without your smart phone. And you might like what replaces it a lot better.