Why the Idea That the Human Mind Is an Illusion Doesn’t Work

There is a simple way to test whether our thoughts are all illusionsSitting in a room with me are some smart people listening to a podcast of neuroscientist Sam Harris. They nod solemnly as Harris tells them that their thoughts are all illusions. No one has free will either, Harris says, both on the podcast and in his 2012 book, Free Will. Sir Francis Crick (1916–2004) said much the same in his 1994 work, The Astonishing Hypothesis.

Harris and Crick are science-trained and Crick is a Nobelist. But popular culture influencers think the same way. The widely-read manga graphic novel artist, Masashi Kishimoto, has a character say in his 2009 work, Naruto,

Every single one of us goes through life depending on and bound by our individual knowledge and awareness. And we call it reality. However, both knowledge and awareness are equivocal. One’s reality might be another’s illusion. We all live inside our own fantasies, don’t you think?

Are these thinkers correct? What is the counter argument?

We who believe our thoughts are real and that we have free will usually respond with philosophy, logic, and common sense arguments. These are powerful responses, but now we have a physical way, using an infinity mirror, to demonstrate that the illusion theory advocates are trapped in a fatal paradox.

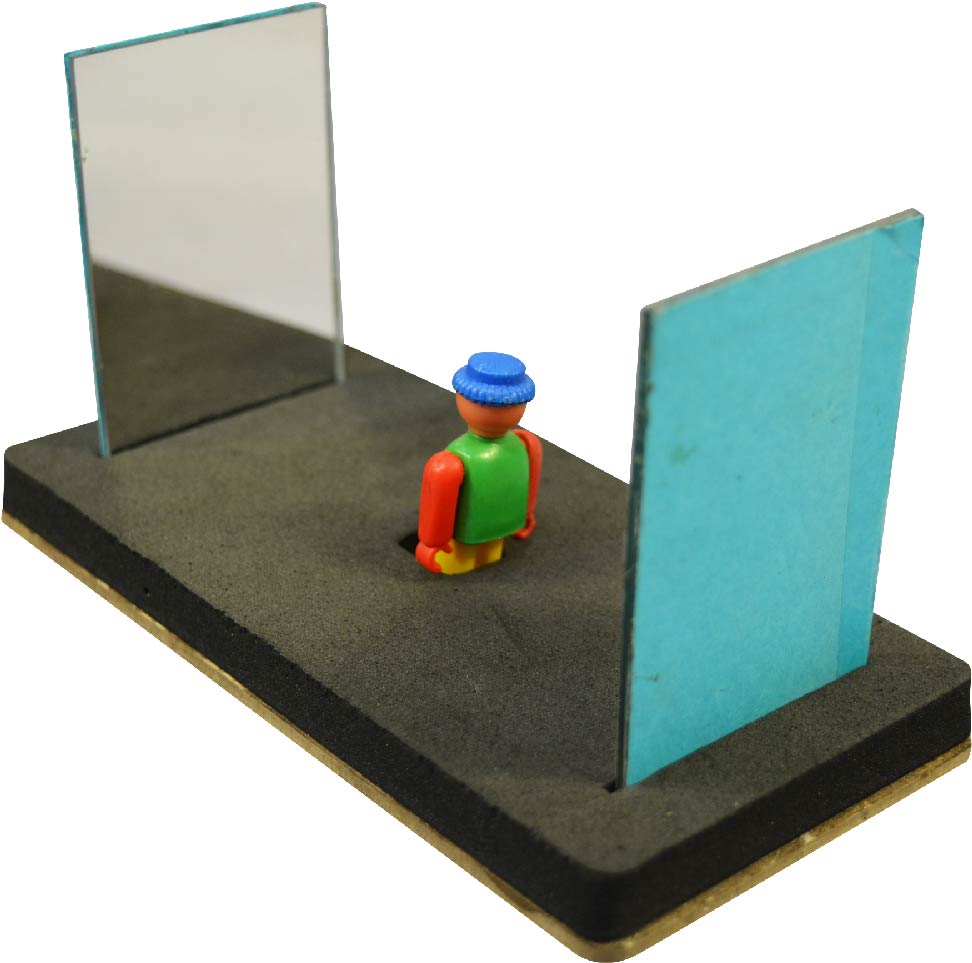

Infinity Mirror Experiment

Set up two mirrors in parallel facing each other so that you can easily stand in the middle between them. (pictured.) Look into one of the mirrors, and you see your own reflection. You will also see your reflection repeated into the distance, as the light from that first reflection is reflected back by the mirror behind you. And then that reflected reflection is reflected by the first mirror, back and forth into infinity.

And, if you are in the picture:

But now, consider what happens when a pretty lady stands in that middle space between the parallel mirrors. Her image reflects repeatedly into the distance, getting smaller, hazier, and darker, as it recedes. Those effects occur because the mirrors cannot perfectly reflect all of the light each time.

The images degrade into a distant, dim, fuzzy, haze. Yes, you can try this at home.

If you believe in the laws of physics and that we humans can perceive external reality, i.e., that our thoughts are at least good estimations of that reality, then the infinite mirror demonstration is predictable, understandable, and reproducible.

If you believe that our thoughts are illusions, however, then you face several challenges.

First, seeing yourself in the first mirror reflection is itself an illusion. There is no reflection in reality. Second, seeing your reflection when it is reflected back, as in the picture of the couple, is also an illusion. There is no actual second reflection in reality. And all of the subsequent reflections of reflections are illusions and not real. The reflections are not occurring. You see them and I see them but they are not there in reality.

Third, if you raise your hand, you’ll see movement in the first reflection but also in all of the other repeated reflections. All of these images are illusions, not realities.

The Non-Logic of Illusions

Unlike logic and physics, illusion theory has no rules. It has no rules by which to predict future illusions. Therefore, illusion theory cannot predict a mirror would reflect your image. It also cannot predict the infinite mirror effect seen in the picture of the lady. If you see the infinite mirror effect, it is your personal illusion only.

Illusion theory has no rule about how physical light reflects off physical mirrors. That means there is no reason why the series of repeated reflections would shrink and degrade as they do into the distance.

Illusion theory does not predict that you will see your hand movement reflected once, more than once, or identically repeated through the sequence of “infinite” reflections.

Illusion theory has no rule of reproducibility. Yet, if you set up the infinity mirror experiment at another time, you will see the same effect.

Illusion theory has no rule about how other observers perceive their illusions. In the picture of the couple, the handsome gentleman is viewing the lady’s reflections. Under illusion theory, there is no reason why he would see the same reflections as she does. Yet he does see them.

Notice another effect in that picture: The reflections are reversed every other time they appear. Each reflection is followed by a “mirror image” reflection of itself, repeating indefinitely into the distance. Illusion theory does not predict that the illusion will produce alternating mirror images.

Uninvolved Viewer Paradox

Expand the experiment by taking a photograph of the infinity mirror experiment, as shown in our picture of the couple. Show the photograph to an uninvolved viewer without explaining it. That viewer will report seeing the infinity mirror’s repeated reflections including the degradation into the distance.

Illusion theory has no rule about perceiving photographs. The uninvolved viewer has no reason to experience the same illusions as did the lady and gentleman. First, there is no reason the viewer would see anything in the photo, as itself, an illusion.

Second, even if the viewer saw the lady and gentleman standing near the mirror in the photo, there is no reason the viewer would see the repeated reflections also. If the repeated reflections are personal illusions, then the uninvolved viewer would have no reason to see a different person’s illusions.

Illusion theory cannot explain or predict the infinity mirror experience at any level. Meanwhile, the laws of physics applied to energy and objects in external reality do explain and predict mirror reflections, the alternating mirror images, and the degrading strength and clarity of each successive reflection. The laws also explain why the experiment is reproducible and why every observer sees the same effects whether in person or in photos.

When someone asserts “your thoughts are just illusions,” we can enigmatically rejoin with: “How does your illusion theory explain infinity mirrors?” Set up actual mirrors, view a YouTube video demonstration, or conduct the thought experiment, and step through the logic:

- Is your reflection in the mirror an illusion?

- Is the infinity mirror experience of an endless receding sequence of reflections also an illusion?

- Is a photograph of the infinity mirror experience also an illusion?

- When another uninvolved person sees the photo and reports seeing exactly what I see, is that an illusion?

At this point the illusion theorist must be able to explain the causation of these experiences. What is the sequence of events that produces the final complex “illusion” in the mind of the uninvolved person? The illusion theory paradox then becomes stark. There is no rational way to explain the causal chain of events leading to the photographed illusion of the infinity mirror. The illusion theory does not survive the infinity mirror experiment.

Notes

The first figure portrayed: Created by Exploratorium. International license. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

The second figure portrayed: Created by YouDo Educational Products, New Delhi, India. All rights reserved. Used with permission.