Phrenology: The Pseudoscience That Just Won’t Give Up

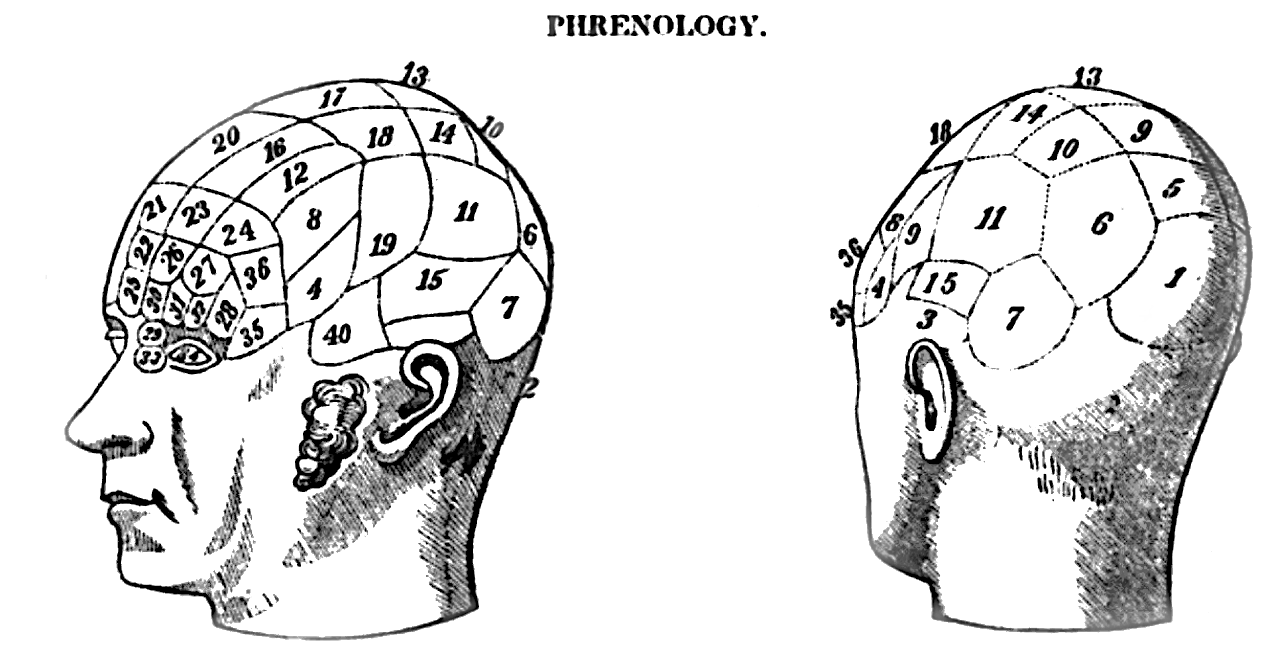

Are we arguing about this AGAIN?Phrenology is the detailed study of cranial sizes and shapes as a proxy for brain size and shape. Practitioners believed themselves to be able to use this information as an indicator of both the character and the mental abilities of the person whose brain was being investigated. Phrenology has been widely discredited, and is thought by many today to be pseudoscience. However, the vestiges of phrenology remain with us today, and are still used to justify various common beliefs and inferences, even by otherwise very educated people.

The most common way that this happens is the use of brain size in the evaluation of the character of human evolution. It is often supposed by researchers that brain size can be used to measure the intelligence of early humans. The ludicrousness of this is clear — if phrenology is wrong, and brain size and shape don’t tell us anything about human character or intelligence today, why would the brain size of individuals from long-dead societies tell us anything? Why would we believe we can draw any correlation at all, when no correlation exists today?

In fact, there are known instances where people with practically no brain mass at all lead perfectly normal lives. One in particular was missing 90% of his brain but was able to lead a normal life, and was married with children, and held down a job as a social worker. A woman who was missing her cerebellum (which has about half of your brain cells) was also found to function normally, although had a history of clumsiness. Recently, MindMatters News reported on a rat which was missing most of its brain, but nonetheless was behaving normally and could solve most puzzles.

That brings us to a more recent story from late last year, where scientists used human genes to make monkey brains bigger. This is reported as a step in the direction towards a “Planet of the Apes” type of situation (based on the movie where apes developed human intellect and took over the planet). Of course, to believe this requires that we believe in phrenology. If making a human brain’s size to be smaller than that of a monkey doesn’t cause them to lose their human intellect, neither will making a monkey’s brain larger than normal automatically imbue the ape with the ability to reason like a human.

It may seem strange that beliefs such as this stick around, and even flourish among educated people. However, this is not the only idea in science which seems to outlive its evidential foundations. The belief that machines will achieve consciousness, that life can come from non-living material, that intricate structures can form solely via natural selection, and that physics represents the entirety of reality — these are all things which are demonstrably false, yet still live on in what Jonathan Wells calls zombie science.

Why is this? It differs depending on the idea. For some ideas, the technical nature of the problems make them difficult to communicate to everyone. For others, the idea had gained so much popularity before it was shown to be wrong that a lot of theory was developed around the wrong idea. For others, the idea is so tied in with common worldview issues that the worldview winds up taking precedence over the data.

And this is not just true of science, but also of mathematics. As I have noted previously, a whole set of practices have been devised in mathematics based on the idea that infinitesimals aren’t well-defined. These practices have remained in place even as the rigorous definitions of infinitesimals have been proved since the 1960s. Even today, the current notation for higher-order derivatives in calculus is very misleading and require kludges to manipulate, despite the fact that better notations that are actually algebraically manipulable are available.

The takeaway point to remember is that groupthink easily happens in any part of life, even science. Scientists are just as prone to popular misrepresentations as anyone else, sometimes even in their own field. Therefore, we should always be willing to ask ourselves whether or not the logic of the claims are based on the actual data, or based on popular misconceptions about what the data means.