Cryptography: Are Non-Fungible Tokens a Scam? Or Can They Work?

By Warren Buffett’s logic, if cryptocurrencies are rat poison squared, non-fungible tokens are rat poison to an infinite power. But is that all there is to be said about them?Introduction: At Expensivity, Bernard Fickser explains that a non-fungible token (NFT) is a unique token in cryptography that represents, say, real estate or art rather than money. Because the tokens have unique identities (non-fungible), they can be bought or sold while reducing the risk of fraud.

So how do they work?: The series is called How Non-Fungible Tokens Work: NFTs Explained, Debunked, and Legitimized (July 30, 2021). In Part 1, he looks at the problems with making NFTs work.

1 Non-Fungible Tokens: Rat Poison Raised to an Infinite Power?

“Poised to radically reconfigure the crypto-asset market, non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, are revolutionizing our conception of money and value, creating not just entirely new markets but even new economies that are able to scale globally and to discover value in undreamt places, relegating to oblivion fiat currencies and old ways of doing business.”

Just kidding. The previous paragraph is a parody (if such is possible) of the hype that in the first half of 2021 has come to surround non-fungible tokens. Indeed, the hype has become so overpowering that it may even defy parody. Non-fungible tokens can have legitimacy, and I’ll discuss how that can be at the end of this article. But for now the overwhelming majority of what passes for NFTs is delusion, fueled by the hope of a quick return and the belief that something can be gotten for nothing (or virtually nothing).

Warren Buffett famously remarked in 2018 that Bitcoin (and by implication all cryptocurrencies) were “probably rat poison squared.” That seems unduly pessimistic given that cryptocurrencies provide a way of securely moving around things that at least look like currency and that in some locales are actually being used like currency. In Venezuela, for instance, Bitcoin provides one way around the country’s corrupt central bank and the hyperinflation it has created. And in early June of 2021, the El Salvador government even approved Bitcoin as legal tender.

But non-fungible tokens are very different from currency. Fungible refers to things that can be interchanged without gain or loss. If you and I swap one-dollar bills, neither of us is better or worse off. If we swap equal amounts of bitcoins, we’re likewise no better or worse off (save for transaction fees). And if we swap the same number of fungible tokens (such as gambling tokens, whether these be physically stored behind a casino counter or digitally stored on a blockchain), we’re likewise no better or worse off.

But non-fungible tokens are not interchangeable in this way. They’re essentially digital collectibles. And even as collectibles, they’re nothing like physical collectibles. If I own a physical work of art, there’s no other physical object in the world that is exactly like it. Distinct medium-sized physical objects (such as can pass as a work of art, in contrast to atomic or quantum-scale particles) have the property that they differ in their constitution and structure in some discernible way (perhaps apparent only with the use of a microscope) even if the difference is minute.

This is important. Setting aside science fiction counterexamples (such as that we’re all living in “the Matrix” and so our entire existence is inherently digital), the real physical world can only be digitized by approximation and never exactly. What’s more, our technology can tell the difference. This is not to say that real-world physical objects can’t be faked. Clifford Irving’s Fake and Anne-Marie Stein’s Three Picassos Before Breakfast testify to the gullibility and incompetence of many so-called art experts. The case of Eric Hebborn, considered the greatest art forger of the 20th century, is particularly revealing about the extent to which the art market may be populated with fakes.

Nonetheless, physical collectibles have built-in safeguards against replication. Even a print-run with multiple copies of the same baseball card, for instance, cannot avoid that each card will show minute differences, even right off the press. Moreover, these differences will increase as the cards end up in individual hands and are thus handled and marred. And even putting them in plastic cases will only decelerate the work of entropy. Anything physical never stays the same but gradually transforms, and, because of entropy, typically for the worse. Rust, for example, lightens cars by about ten pounds every year (see Jonathan Waldman’s Rust: The Longest War).

But digital collectibles, whatever else they may be, are—without exception or remainder—digital files. In other words, they’re just strings of bits. As a string of bits, a digital file has a fixed number of bits, with the bit at any location in the string having a definite value of either zero or one. What this means is that digital collectibles can be copied exactly, which in turn means that you’re no better or worse off owning a copy in place of the original (whatever “original” in a digital context may mean).

Compare this to owning an oil painting. If I own a copy of the Mona Lisa, it is a verifiable fact that I don’t own the original (which hangs in the Louvre). Even if my copy is stunningly close to the original, and perhaps more emblematic of Leonardo da Vinci’s technique and brushwork than what’s in the Louvre, provenance (i.e., a thing’s history) will demonstrate conclusively that the painting in the Louvre and not my copy is the original. Moreover, I know that this copy holds vastly less value and influence than the original. That’s just the way it is with physical collectibles, and it applies as well to baseball cards, coins, stamps, etc.

But with a digital collectible, the file anyone owns is indistinguishable from the other copies out there. With physical collectibles, copies are always discernibly different. With digital collectibles, on the other hand, the copies are exact (error correction protocols guarantee as much). So what’s the point in paying extra for a digital collectible that takes the form of an NFT? By Warren Buffett’s logic, if cryptocurrencies are rat poison squared, non-fungible tokens are rat poison to an infinite power.

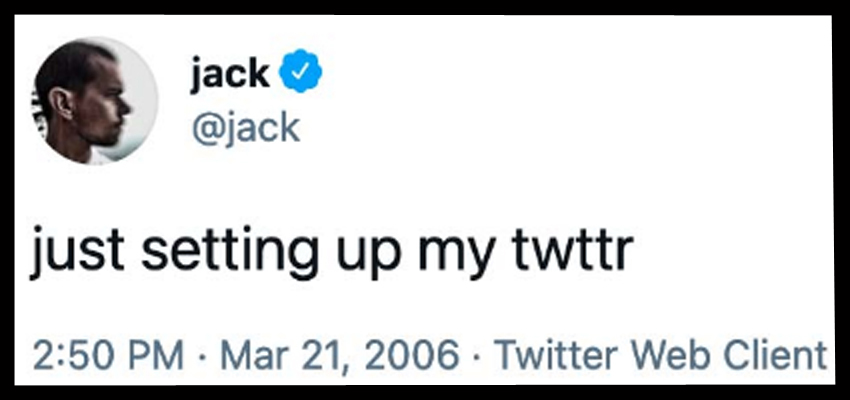

Not so fast, say proponents of NFTs. The issue is not replication but scarcity. Blockchain technology allows for digital collectibles to be scarce even if they are replicable. Granted, a digital file can always be copied exactly. But a digital file on a blockchain when cryptographically signed by some person or organization of standing (such as Jack Dorsey in tokenizing and then selling his genesis tweet) can be scarce, maintain its scarcity, and thereby achieve value that is negotiable and thus a medium of exchange.

But which blockchain? There are many blockchains. What is to prevent someone from uploading the same NFT on multiple blockchains (less of an issue for now because Ethereum seems to run all the NFTs)? What is to prevent someone, once having uploaded an NFT on a given blockchain, to promise not to upload anymore copies, but then to break the promise and, in effect, increase the print run?

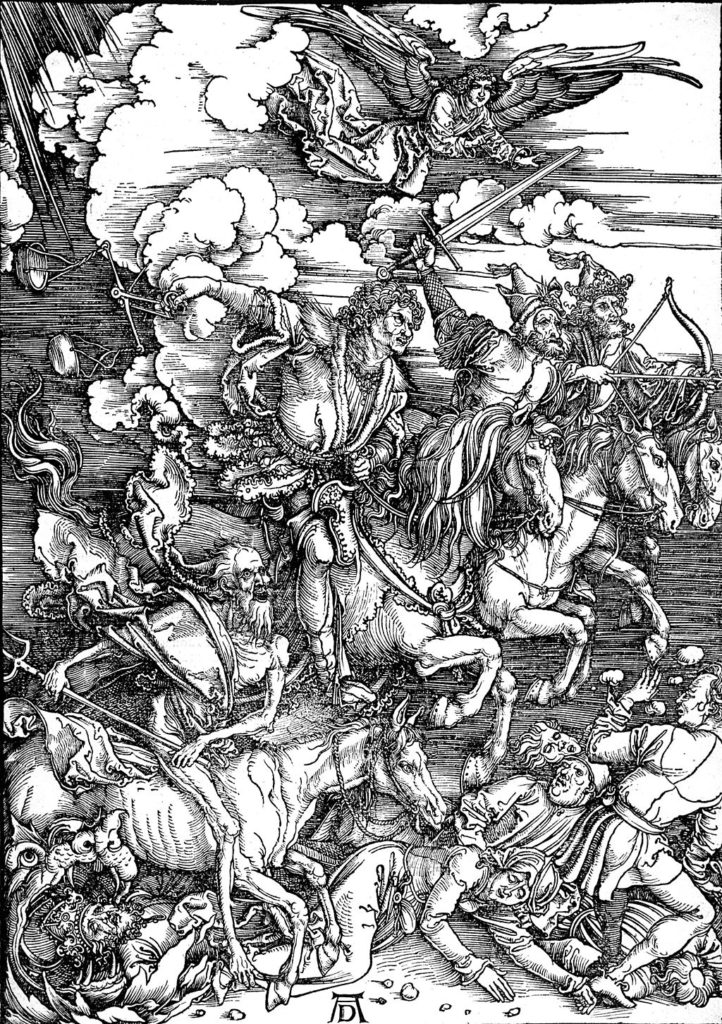

For comparison with real physical objects, consider the woodcuts of Albrecht Dürer. As Dürer produced these woodcuts by repeatedly applying ink to his carved wood blocks and imprinting them on paper, they would become increasingly fuzzy as the wood carving wore away with each successive imprint (real-world entropy again). Even long print runs could therefore meaningfully distinguish earlier from later imprints for Dürer’s woodcuts (the earlier ones being sharper and thus more valuable). Ditto for copies of physical art objects in general.

Digital collectibles, by contrast, can be copied with complete fidelity within and across blockchains. Moreover, they can be cryptographically signed again and again. At best, some sort of social validation can control their proliferation. Thus, in the case of Jack Dorsey’s genesis tweet, it’s not the tweet itself, represented as a digital file, that’s so important in gauging its value as his standing as the founder of Twitter and author of the tweet, and his ability to validate its digital transfer from himself to another party.

But whatever you can do digitally once, you can do digitally again. Unlike physical processes, which typically are irreversible (entropy again), digital processes are generally reversible, and where they are irreversible, there’s often a workaround, such as with a computer game where you simply restart it from any desired point in the history of play. In consequence, we have no technological guarantees that Dorsey’s genesis tweet will not be retokenized by him as an NFT. Instead, the only constraint on proliferation is Dorsey’s promise not to do otherwise and the social norms that would hold him to that promise.

In this introduction, I’ve been unduly negative about non-fungible tokens. There is in fact a core idea underlying NFTs that is potentially powerful and revolutionary. But the devil is in the details, and the details, as they are presently being worked out in the theory and practice of NFTs, are making NFTs into a caricature of what they might be. NFTs such as CryptoKitties, Beeple art, and Jack Dorsey’s first ever tweet are trivial, mediocre, forgettable. Insofar as they aspire to be art, they’re kitsch.

If NFTs are going to have a future, they need to do better.

Next: 2 Digital signatures in digital marketplaces

Part 1: Cryptography: Are non-fungible tokens a scam? Or can they work? By Warren Buffett’s logic, if cryptocurrencies are rat poison squared, non-fungible tokens are rat poison to an infinite power. But is that all there is to be said about them? Blockchain technology allows for digital collectibles to be scarce even if they are replicable, thus creating value, like Jack Dorsey’s famous initial tweet.

Part 2: Can digital signatures protect NFTs in digital marketplaces? The concept of owning an NFT on a blockchain is specific to the blockchain with no legal force in society at large. While NFTs are new, the debasement of value by proliferating copies whose marginal value is close to zero has a long and ignominious history.

Part 3: How to create non-fungible tokens (NFTs), simplified. While still deeply skeptical of what ownership of an NFT really means at present, Fickser decided to experiment with creating, buying, and selling NFTs. Bernard Fickser offers a step-by-step explanation, offering an original montage of the Democratic primary in Iowa in 2007 for sale as an illustration.

Part 4: NFTs: You bought one. But do you really own it? Could you ever? Right now, the non-fungible tokens markets leave a lot to be desired as a business proposition, Bernard Fickser explains why. The current NFT regime features no limit on proliferation, no guarantee of scarcity, and terms that disclaim any accountability on the part of the NFT market.

Part 5: In the digital world, what does “scarcity” mean? For a digital artwork like Beetle’s Everydays, which sold for over $69 million, a number of methods are used to prevent copying, thus ensuring uniqueness. Three methods used to ensure uniqueness include partial availability (for fair use), digital marking, and algorithmic immutability (like blockchain).

Part 6: What makes NFTs valuable? What does it mean to own one? In the case of non-fungible tokens (NFTs) on the Ethereum blockchain, actual ownership with legal standing is never in fact transferred for the underlying digital file. Bernard Fickser points out that the NFT literature is filled with equivocations about the meaning of the word “own” as it relates to NFTs.

Part 7: How can non-fungible tokens (NFTs) be made to work better? Bernard Fickser offers twelve steps to handling NFTs in a way that dispenses with cryptocurrency-based blockchains and works in ordinary online marketplaces like eBay. In Fickser’s view, NFTs can work if they avoid self-serving cryptocurrency blockchains like Ethereum and enable real-world legal transfers of ownership.

Also: Jonathan Bartlett’s response: Blockchains have NFTs unnecessarily tied down. New ideas propose severing the accidental relationship between NFTs and blockchains. For NFTs, the blockchain is actually reducing the value of the NFT, as it introduces additional dependencies and costs for maintaining NFTs